Abraham Maslow once said, "If the only tool you have is a hammer, you treat everything as though it were a nail."

In this essay, I will depart a bit from my review of the research. In this essay, I will focus more on a critique of it and on the limits of scientific method in social science research.

Modern social science research has been dominated by quantitative methods of research. This is true of CMC research as well. Chi square, standard deviations, co-efficients of correlation are everywhere. Indeed, it's as if it can't be counted, it doesn't count. Quantitative research has become the only tool in the toolbox and ever research question has become a nail.

Certainly scientific method and quantitative studies have their place. However, sometimes they leave important questions unanswered or, worse, they appear to lead to an answer which later is determined to be obviously wrong.

There are limits to scientific inquiry and quantitative research. Let's take an everyday example. If you wanted to know what I had for breakfast, you could pump my stomach and analyse the results. If you wanted to be less intrusive, you could sit at my breakfast table, measure everything on my plate and watch me eat it. However, if you wanted to know if I enjoyed my breakfast, you would have to ask me. It would be unscientific, subjective, and imprecise, but it would be the best way to get the answer.

Of course, you could do a survey of 1000 people and find out if they liked a certain food and if a majority of them did, that would mean I did as well. But you see the problem, that assumption would probably be even more unreliable than asking me. It would be more scientific, more precise, and more prone to error. You used a hammer to saw a piece of wood.

So, what's the alternative? Unfocused theorizing? Purely subjective reporting of impressions? Certainly not. We need systematic ways to understand the functioning of CMC and virtual communities without depending entirely on quantitative measures.

One may argue, correctly, that qualitative measures such as phenomenology, participant-observer, hermaneutics and other forms of naturalistic inquiry are limited in terms of broad applicability. For instance, the anthropologist studying a single tribe by living with them for several years may understand that tribe well, but not necessarily the one on the other side of the hill.

This is true. However, any avid reader of quantitative research in the social sciences knows that simply because a study is statistically-based doesn't mean it necessarily has wide applicability either. For instance, much research about online education is based on the experiences of a single class. Additionally, in most studies, the majority of subjects are students at major universities where the studies are being conducted. Generally, social scientists know a lot about white, middle class, college students, but not much about anyone else.

What is true in terms of size and diversity of subjects in the studies is also true in terms of time. Many studies of virtual communities are more like snapshots than movies. They often focus on a few days to a few weeks of messages. These messages are lifted outside the social context of the virtual community and may be misunderstood because of that lack of context.

So, what are some alternatives?

First, participant-observer studies. Popular for years among cultural anthropologists, the participant-observer lives with the cultural group they are studying. It may take several years to fully understand that group. Certainly, they stay around long enough to understand the shared history of the group. It is a tricky approach. the participant-observer must be in some way engaged in the life of the group, but must always remain somewhat aloof from the group. Nevertheless, by developing a careful approach to notekeeping and self-discipline, the participant-observer can often understand many things that the quantitative researcher might miss.

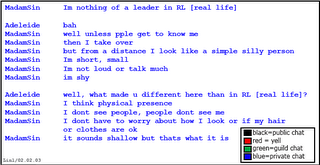

In CMC research, being a participant-observer, could mean being part of several online communities, interacting with them, but maintaining a certain amount of social distance from them. Notetaking would include not only content analysis of specific messages in the group, but also recognizing and recording interaction patterns between group members, tracking the social history of the group, watching the reaction of long-time group members to "newbies," and paying attention to the cycles and "seasons" of group activity.

A second approach, suggested by Quentin Jones (1997), is called cyber-archeology. Jones postulates that virtual communities exist in virtual settlements and they leave cyber-artifacts behind. These artifacts include communication structures, nonverbal aspects of an essentially verbal medium, standards of practice and terms of service for groups as well as behavior patterns of members of the group. While Jones lacks specificity concerning procedures for conducting a cyber-dig, it is an intriguing idea.

A third method is the phenomenological method. In the phenomenological approach, the researcher conducts in-depth interviews with a few subjects to gain a deep understanding of the experience of that person from the inside out. Rudestam and Newton (1992) put it this way:

When phenomenology is applied to research the focus is on what the person experiences in a language that is as loyal to the lived experience as possible (Polkinghorne, 1989) Thus, phenomenological inquiry attempts to describe and elucidate the meanings of human experience more than other forms of inquiry, phenomenology attempts to get beneath how people describe their experience to the structures that underlie consciousness. (p.33)

Early erroneous observations which denied the existance of true community online or discounted anecdotal evidence of intimacy bonds existing in cyberspace might have been avoided if someone had thought of the simple expedient of actually talking to some netizens in depth about their online experiences.

We can learn much from quantitative approaches to CMC research, but we must not forget the value of qualitative approaches as well. There is a place for a hammer, but also one for a scalpel.