Online Worlds as "Third Places."

I must admit that I skipped over this article the first time I saw it. I'm not much into computer gaming. Okay, I have a chess program and a Scrabble game on my computer, but when it comes to fighting wars with eight-legged dragon thingy's in some dark "sword and sorcery" virtual world, I yawn and leave it to the kids.

However, my involvement with the "sim" environment of Second Life has piqued my interest in these shared environments or what Constance Steinkuehler and Dmitri Williams (2006) refer to as "Third Places." In their study entitled "Where Everybody Knows Your (Screen) name: Online Games as "Third Places" the researchers contend that the simulated worlds of massive multi-user online games (MMO) serve as "third places" for social interaction and as a place to build social capital in an environment outside that of the other two places of home and the workplace (or school).

They define third places based on a model developed by Oldenburg (1999). A third place is a place of interaction outside of those provided by the home (not necessarily the physical building but the social network of family relationships) and the job. Third places are not unique to cyberspace. Indeed, churches, clubs, support groups, even gyms, pubs and coffee shops have provided a venue for such relationships in the past. However, Oldenburg (1999) notes the decline of social engagement in such "brick and mortar" settings. Steinkuehler and Williams (2006) summarizes this phenomenon in the article:

In his seminal text, Oldenburg (1999) documents the decline in brick-and-mortar

"third places" in America where individuals can gather to socialize informally

beyond the workplace and home. The effects are negative for both individuals and

communities: "The essential group experience is being replaced by the

exaggerated self-consciousness of individuals. American lifestyles, for all the

material acquisition and the seeking after comforts and pleasures, are plagued

by boredom, loneliness, alienation" (Oldenburg, 1999, p. 13). Recent national

survey data appear to corroborate this assertion, with census data indicating

that television claims more than half of American leisure time, while only

three-quarters of an hour per day is spent socializing in or outside of the home

(Longley, 2004).

However, engagement online is on the increase. Some of this takes place in text-based virtual environments like chat rooms, discussion forums, blogs and email discussion lists. MMO's however, differ significantly from these other types of online communities in that they create a visual, virtual world in which you assume a character represented by an avatar that you manipulate in that world as if she/he/you lived there. Jane Dragonslayer isn't just a screen name, she is the shapely blonde in chain mail sitting on the other side of a table in a pub her conversation combining discussion of dragon repellent, lag time in loading a certain region of the world, and how her boss is a jerk.

These third places are actual places (albeit digitally produced on a screen.) The better sims provide a three dimensional environment where you can walk around objects, pick them up, modify them. You have pubs, clubs, castles, houses, town squares, cafes, inns and forums where you can meet and greet others. It is a much richer environment than a text-based chat room.

Characteristics of Third Places

Given these dynamics the authors say that such games and simulated environments meet the criteria set forth by Oldenburg (1999) for third spaces. He set forth eight characteristics of these spaces. These virtual worlds share most of them.

Neutral ground. It's like the corner cafe. It's a shared space without obligations or entanglements. You hang out there and chat about the local politics, but nobody is going to call you if you fail to come in for breakfast for a week. These virtual worlds are often "game universes." The player doesn't feel an obligation to engage in the game regularly if they don't want to. Unlike home or work or even involvement with a service club or religious organization these are worlds without responsibility.

Leveler. One's rank or status in Real Life (RL) is irrelevant in these worlds. You build your own status here according to the social rules of the virtual world. In the game worlds, you do so by playing the game better than others, move on to higher levels, assume greater powers. In the "sim" community worlds like "Second Life" you build status by the house you build, the virtual money you earn, how you refine your avatar, and what you contribute to the virtual world.

A person with a modest social status in RL can rise to a high level of respect in the virtual world.

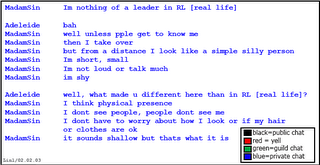

The authors of the study tell of a woman who is a "guild leader" in one game online but considers herself a cypher in RL. Here's a portion of their chat with her:

The authors comment about this:

Here, a renowned guild leader in Lineage I explains how avatar-mediated social interaction enables her to play a leader in the virtual world in ways she is typically unable (or, more accurately, not allowed) to in "real life." This sense of moratorium from stratified daily social life enables MMOs to function as kind of level playing field and, in part, may explain some of their popular appeal: Like sports, MMOs appeal to people in part because they represent meritocracies otherwise unavailable in a world often filled with unfairness (Huizenga, 1949). Players are able to enter a world in which success is based not on out-of-game status but on in-game talent, wit, diligence, and hard work.

Conversation is the main activity. Just like the local gossip at Mom's Cafe on Main Street, the virtual worlds online emphasize conversation. Even the role playing gaming sites have common areas such as pubs and town squares where plans are made for the mission and people just sit back and chat. Whether it was talking around a Neolithic campfire about the bison hunt or chatting in a virtual club about your new laptop, conversation binds cultures together wherever they form.

Low Profile. Third places are typically homey. You don't hang out at the four star restaurant to sip coffee and catch up on what happened at last night's council meeting. In RL third spaces tend to be unpretentious. The authors note, though, that in virtual game worlds the locals are decidedly fantastic. This is one place where the MMO's depart from the criteria. Yet, do they really? I would propose that the environment is "homey" in the ultimate sense of the word. You are at home when participating. It's not what's on the screen, but how much one feels like they are in a safe, familiar environment. What gives those feelings more than your own house? While one might "lose" oneself in the game, one is always still aware of the real world surroundings.

Also, some of the non-adventure-game sim worlds like Second Life and The Sims online are decidedly homey. Sure some people build castles, but most build homes. They may have a bit of weirdness, like the one next to my virtual property at Second Life which is an oval on top of a tall column with a teleporter pad at the bottom to send visitors to the top. But the house on the other side is a ranch style suburban abode and mine is a Swiss chalet. So, the hominess is emerging.

The Mood is Playful. Seriousness is discouraged in third places. The mood is light and playful. Jokes, word play, flirting abound. In this way, the virtual worlds are different than other types of online communities in which intimacy may develop quickly (see previous post on hyperpersonal communication). Maybe it is the cartoon look of the online worlds or the fact that many are game oriented (how much intimacy occurs while you are playing monopoly), but compared to my experience in email discussion groups and discussion forums, the mood is definitely lighter. Again, this is similar to many 3D third places. Bars, cafes, social clubs, gyms also discourage serious conversation. Everything is kept light and playful. "The gang" at the club is not a support group.

The Regulars. A third place has a regular clientele. Like the bar on the TV show "Cheers", you go "where everybody knows your name" or screen name in this case. At the very least you know the regulars on sight. There's the guy flirting with the waitress using the same lines over and over, the woman who is always upset about something happening in local politics, the guy who brings a book to read, but ends up joining in the conversation instead. The same thing occurs in virtual worlds. I wasn't in Second Life two days before I had a half dozen people in my friend list.

The regulars welcome newcomers, engage in in-world talk, know the ropes of the game, guide novice game players, and sometimes form volunteer groups which act as a sort of virtual "homeowners" group to help guide the future development of the virtual world.

Home Away from Home. Third places create a sense of rootedness. The local cafe where I hang out a lot in RL expects to see myself and my family regularly. When my Dad passed away, many of the patrons expressed their sympathy even though the obituary hadn't appeared in the small weekly newspaper yet. When my Mom hurt her knee and was unable to make it to the restaurant, the waitresses and patrons asked about her and sent messages of concern.

Online environments also create such homes away from homes. If a regular doesn't show up on line for awhile, private emails or IM's are often sent to follow up. Some virtual worlds like Second Life have taken the home away from home concept to it's logical conclusion allowing people to "buy" land and "build" virtual homes where you can invite people to "sit" and visit.

This article is fascinating and is much richer in information than I can give in this post. I really advise that you read this one, if you have any interest in online community building.

References

Oldenburg, R. (1999). The Great Good Place: Cafés, Coffee Shops, Community Centers, Beauty Parlors, General Stores, Bars, Hangouts, and How They Get You Through The Day. New York: Marlowe & Company.

Steinkuehler, C., and Williams, D. (2006). Where everybody knows your (screen) name: Online games as "third places." Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 11(4), article 1. http://jcmc.indiana.edu/vol11/issue4/steinkuehler.html

1 Comments:

Nice homework assignment, I will get right on it. Very interesting topic.

Post a Comment

<< Home